Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg (released on December 15, 1985), for which he served as both screenwriter and director, is an animated film that closely resembles a “painting” to be appreciated in a museum setting. However, it is not what one would typically call an art animation. Oshii himself stated upon the film’s completion that it was by no means intended to be an incomprehensible art film. Rather, he hoped that even innocent young girls and mothers would watch it and discover a new kind of sensory experience. He declared that this, too, is a form of entertainment.

In the case of this film, anyone approaching it with the usual expectations of entertainment—where characters lead the story—will likely be confused by its many enigmatic elements. Yet, by watching the screen with an open mind, immersing oneself in the music and soundscape, and processing the various elements internally, the viewer can arrive at a new form of self-discovery. One of the director’s intentions was precisely to awaken the primal memories that lie dormant deep within the human soul. As a result, the impression the film leaves can vary drastically depending on the viewer. Above all, I encourage you to fully immerse yourself in the overwhelming, avant-garde sensations this work offers—experiences unlike any other film.

Here, let us briefly look at the background of Angel’s Egg. The era of home video and the new medium known as OVA (Original Video Animation) began exactly two years prior, at the end of 1983, with Dallos, directed by Mamoru Oshii (co-directed with Hisayuki Toriumi). At the time, the monthly magazine Animage, published by Tokuma Shoten, was shifting its focus from character-driven content toward a more auteur-driven approach to evaluating anime. Following this editorial direction, and in the wake of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), which was also produced under the initiative of the publisher, Animage began exploring the creation of anime works led by strong authorial vision. In this context, Angel’s Egg was produced—with Animage editor Toshio Suzuki serving as producer, just as he had on Nausicaä—as one of the most artistically ambitious works ever marketed explicitly for its auteur sensibility.

That said, producer Toshio Suzuki and others involved in the project had initially hoped for a more accessible, entertainment-oriented film. However, after Mamoru Oshii personally persuaded the upper management at the company using his own words and vision, they prioritized a stance of “betting on what the creator truly wants to make.” According to Oshii himself, the production adopted a royalty system modeled after that of original, single-volume manga publications—a highly unusual arrangement. This reflects a fundamentally different kind of relationship between publisher and anime creator compared to today. In this sense as well, Angel’s Egg stands as a nearly one-of-a-kind feature-length animation.

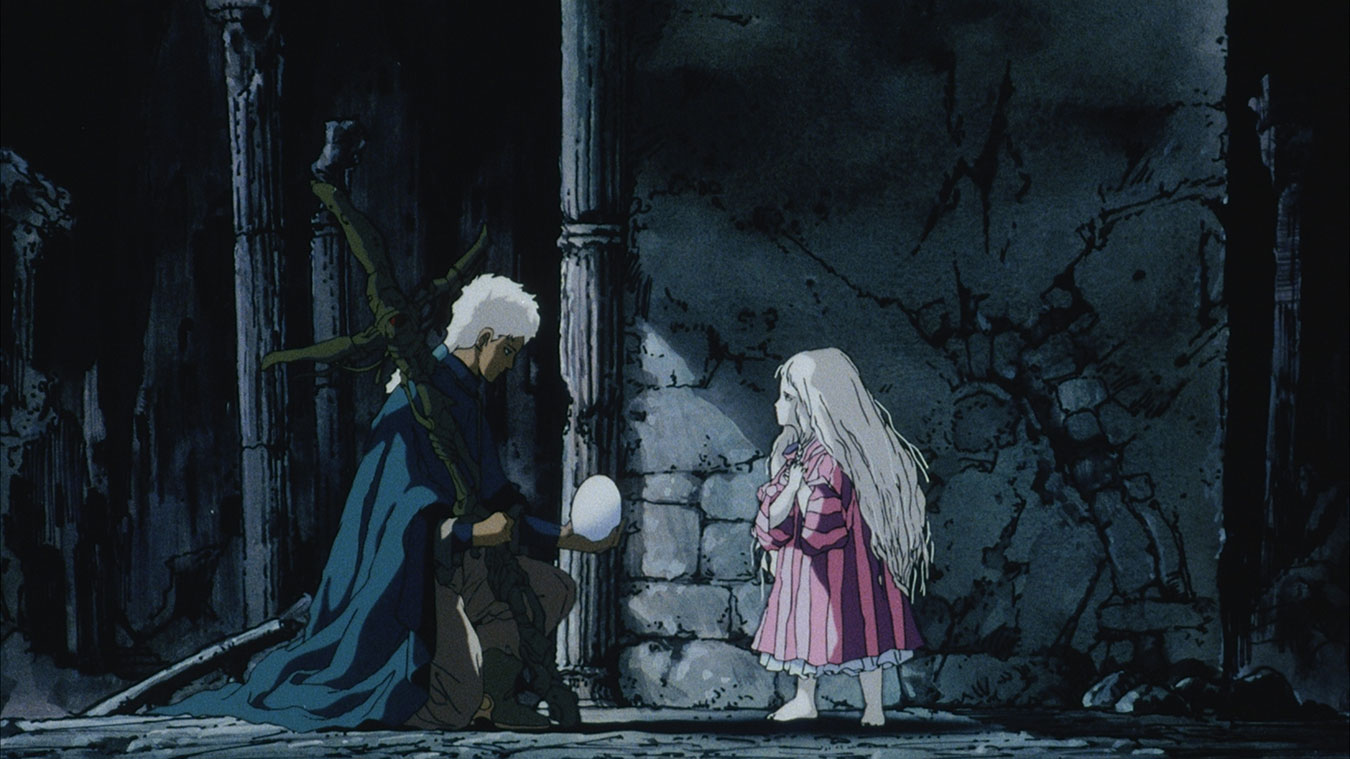

The story of Angel’s Egg is, in fact, remarkably simple. A young girl, cradling an egg, wanders alone through the flooded ruins of a desolate, old European-style city, drained of color. Eventually, a convoy of tanks appears, from which a boy carrying a cross-shaped weapon disembarks. What will their encounter bring? What lies within the egg? What is the connection to the “bird” the boy seems to pursue? The film offers almost no clear explanations or causal relationships. Instead, it unfolds through symbolic imagery and highly artistic visuals, accompanied by only the sparsest fragments of dialogue.

Typical commercial anime follows a convention of rapidly cutting between shots—usually around three seconds each—that depict characters’ emotions such as joy, anger, sorrow, or excitement in a symbolic manner. This fast-paced editing keeps viewers continuously stimulated, leaving little room for reflection and drawing them quickly into the story. Showing shots for longer periods risks exposing the fact that these are merely flat images. In contrast, Angel’s Egg frequently employs long takes, depicting both backgrounds and characters with richly detailed visuals, carefully layering a slow-moving “spatiotemporal” experience. The longest single take lasts 150 seconds, and the entire 80-minute film contains only about 400 cuts—averaging 12 seconds per cut. By comparison, Arion (1986), a feature-length film released around the same time and directed by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, runs 118 minutes with 2,000 cuts (an average of 3.5 seconds per cut). This clearly demonstrates that Angel’s Egg offers a much slower perceived passage of time compared to typical anime (source: Animage [Tokuma Shoten], November 1985 issue, “First Meeting Dialogue: Yoshikazu Yasuhiko vs. Mamoru Oshii”).

Oshii has stated that his approach was to “keep the viewer in a state of tension, right on the edge of boredom—so bored they could fall asleep—but still offering subtle, ongoing emotional stimulation.” This method served a higher purpose: to awaken something deep within the viewer’s mind. It is precisely this stance—inviting the audience’s intellectual engagement or stirring their subconscious—that may represent the film’s greatest mission, now revived in a clearer form after forty years.

As of 2025, when stimulus-packed anime continue to be mass-produced under the banner of "IP strategy," and discussions focus more on market size and profit than on the content of the works themselves, this film seems to pose the critical question: "Is this really okay?"

Having withstood the test of 40 years, the work delivers a solitary yet resolute statement—"Animation has other possibilities and functions." While there's a sense of frustration that its value was rediscovered overseas rather than at home, the remastering in 4K and HDR now brings its originally intended aesthetic sophistication and artistic quality into sharp relief. This will no doubt lead to a domestic reevaluation, particularly among younger generations who remain untainted by commercialism.

The gateway to the film’s artistic elements lies in the imagery conceived by Yoshitaka Amano—who co-developed the original concept with Oshii and also served as art director—the aesthetically rich spaces crafted by Shichiro Kobayashi, who oversaw art direction and layout supervision, and the meticulously detailed animation brought to life by animation director Yasuhiro Nakura.

These elements interweave tightly, creating a dense and weighty fabric of visual information that gives rise to the work’s artistic depth. This is the decisive difference from the countless generic anime productions. Each and every frame has been crafted to be appreciated as a "moving painting."

At the time, most OVAs were produced on 16mm film in standard size, assuming playback on video decks. Oshii once clearly stated, "I believed that shooting on 35mm film in the Vista size, which is used for movies, would ensure the work’s longevity." That strategy paid off with the 4K remastering four decades later.

Let me also provide some clues to help with appreciating the work. It is well known that Mamoru Oshii frequently revisits the same motifs in his works. Angel’s Egg, as a turning point in his career as a creator, has the character of a kind of exhibition of such motifs. Here, drawing on comments made at the time of its original release in Animage magazine, I will present a few examples explaining why these particular motifs were conceived.

First, the “Christian motifs,” with the Bible foremost among them, were always present in the themes of books and films that Mamoru Oshii had been exposed to since his youth, and they have a deep connection to Japan’s modern mass-consumption society. The “angel fossil” later appears in the manga Seraphim: 266613336 Wings (co-authored with Satoshi Kon), but this element was originally repurposed from a project for Oshii’s version of Lupin the Third, which fell through just before this work.

Although a “messenger of God” is supposed to transcend physical phenomena, it paradoxically transforms into a tangible “fossil.” This great contradiction can also be interpreted as “proof of the angel’s existence.” The fusion and conflict of such opposing elements form the foundational tone of this film.

The concept of "Noah's Ark" is explained in the story through direct references to the Bible, and the motif of birds is deeply connected to it. The "Ark" also plays a key role in the grand set piece revealed at the climax of the film. This is because the origin of the work lies in a moment when Oshii was looking out over the Ring Road No. 8 from his balcony at night and thought, "Wouldn't it be amazing if a majestic ark came into port here?" Based on that idea, the project was initially conceived as a slapstick comedy: “At a convenience store, strange and mysterious people are waiting at 8 p.m. for the arrival of an ark, when a girl carrying an egg walks in.” However, with Yoshitaka Amano joining the project, the Japanese character traits and comedic direction were discarded in favor of a more artistic approach. Later, the motif of the "Ark" would be revisited in Mobile Police Patlabor: The Movie (1989), once again paired with biblical themes.

The fish that swim as shadows across the walls of buildings are also projections of a fantasy—of fish swimming beneath the concrete surface of the same road. The silhouette of the fish is that of a coelacanth. Throughout the film, fossils of prehistoric creatures that are fused with and fixed into buildings appear repeatedly. In contrast to these, the "living fossil" (the coelacanth) stands out sharply. The ruined setting of the entire world reflects a vision of the future that Mamoru Oshii had imagined since his high school days while riding the train to school. It shares the same roots as the "ruined Tomobiki Town" from his previous work, Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1984).

The depiction of an enormous stone slab resembling an evolutionary tree reappears in the climax of GHOST IN THE SHELL (1995). This slab symbolizes the vast amount of time required for biological evolution, petrified into stone. If we consider that at its center lies the "Angel’s Fossil," it brings to mind the film’s intention to encapsulate time. The countless bottles arranged along the spiral staircase also indicate that time within the story does not flow linearly. Furthermore, this arrangement evokes a double image with the DNA double helix—essential to biological inheritance and evolution.

Many of these motifs are deliberately arranged to gradually evoke the feeling that, "although I’m seeing this for the first time, it’s as if I’ve known it since before I was born."

For younger viewers with less life experience, that sensation may resonate even more deeply—so I hope they will cherish it.

Of course, after watching the film, viewers are free to interpret it however they wish. Upon rewatching it myself (and admittedly, this may be a rather crude interpretation), I began to see the “egg” the girl carries as a symbol of the potential of animated cinema. In the end, when cracked open, that potential turns out to be empty. And yet, at the same time, the more mature version of the girl releases countless bubbles upward—toward the sky, which suggests hope—and those bubbles seem to become new “eggs.” In the real world of 2025, many such “eggs” are floating on the surface. But do they contain anything inside? Or are they empty too?

Regardless of the director’s original intention, the film left me pondering such questions.

To conclude, I’d like to highlight the following remarkable comment made by Mamoru Oshii at the time of the film’s release:

“What I was hoping for was that people would become aware of some kind of primal emotion flowing deep within themselves—something ancient in origin—and in doing so, discover a kind of unexpected aspect of who they are. I believe that, too, is a form of entertainment.

In that sense, I want to think of entertainment in a much broader way.”

With the 4K remastering, the “pressure” exerted on the core of our five senses has been intensified, resulting in an overwhelming visual experience.

By immersing oneself in this fictional time and space, I sincerely hope that viewers will sense the possibilities of entertainment and animated cinema—a timeless yet ever-renewed question posed to us all.

References (All from Animage Magazine, Tokuma Shoten)

・"Director Mamoru Oshii’s Work: Angel’s Egg – An Invitation to Its Mysterious World (3): The Legend of Noah’s Ark," Animage, September 1986 issue.

・"First-Time Dialogue: Yoshikazu Yasuhiko VS Mamoru Oshii – What Does 'Artistic Voice' Mean to a Director?" Animage, November 1986 issue.

・"Angel’s Egg GUIDE BOOK," supplement to Animage, December 1985 issue.

・"What Can Anime Really Do? – Six-Night Teach-In Event with Mamoru Oshii at Cineka Omori," supplement to Animage, May 1986 issue.

(Dialogue between Mamoru Oshii and notable figures such as Shoji Kawamori, Ryu Mitsuse, Shusuke Kaneko, Akiyoshi Imazeki, Toshiharu Ikeda, and Hideo Osabe.)